From Frenštát, Moravia, to Fayette County, Texas — A Chronicle of Two Brothers:

Jan and Ferdinand Přibyl

Bette Stockbauer

(This article was originally published in the Fall 2007 edition of Kosmas)

“…[A]nd to my friends across the ocean,

“Already the eighth month is going by since we have finished our rather difficult journey across the immense expanse of the ocean and up to now there isn’t one thing that would cause me to be very surprised; I ascribe this to the circumstance that I have not immigrated out of carelessness but due to certain principles and after sound and mature reasoning and deliberation in order to establish a better future not necessarily for myself but for my posterity; that is why I have determined and decided to sacrifice the remaining little bit of my life, and I have been prepared for much worse than the lessons learned so far by direct experience.

“I hope that my story is going to serve as a good gauge because I am not writing out of fear or for gain but to describe things as they really are in themselves; I presume that people know me as a man who dislikes empty and small talk and despises lies and therefore they won’t dispute the veracity of my rendition.” — Jan Přibyl/ Fayette County, 20 June 1874.

These are the words of my paternal great-grandfather, Jan Přibyl, in an early letter written from Texas to his brother, Ferdinand, and friends still living in northeastern Moravia, expressing his determination to make a better life for his family and descendants in his new homeland of America.

Because of the avid genealogical research done by my mother, Elizabeth Stockbauer, her acquisition of family documents and seeking out of translators, our family has about 250 letters written between Jan, Ferdinand, and several relatives and friends. Many of the letters Jan’s family received from Europe were stored in a shoebox, safely guarded as a family treasure, and then handed down through three generations to a great-granddaughter, Mary Lou Urban. Others came into the possession of Elizabeth, including a notebook of Jan’s with rough drafts of letters written between 1874 and 1883. These drafts have given us a record of Jan’s side of the correspondence.1

Here we will relate the story of these two brothers, using excerpts from their writings to tell of occurrences on both sides of the Atlantic: in Europe the difficulties with living under the oppressive and unsettled conditions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 1800s, and in America the similarly challenging conditions of setting up a new life on the untamed prairies of central Texas. In the letters we find not only copious descriptions of the daily lives of both families, but also philosophical interchanges, political and social commentary, and advice for the new or potential immigrant. There are heartbreaking passages from both brothers when they describe almost unbearable events and burdens in their lives.

Further, they speak poignantly of the immigrant experience itself: for Jan, the challenge of the unfamiliar and questioning of decisions made, for Ferdinand, the pull between the old country and the new, the fear of leaving a settled, though difficult, existence for an uncertain future. For both there is the ongoing pain of separation, the deep desire for freedom driving their actions, and the often cruel price that is exacted to achieve the attainment of that precious goal.

Jan and Ferdinand Přibyl were born in Frenštát, Moravia, Jan in 1831 and Ferdinand in 1840. It is probable that Jan worked in the textile trade, an occupation that began to be marginalized in the 1850s because of industrialization. Since the economy of the area was dependent on this industry, the loss of employment resulted in a widespread depression. Narratives from emigrants fleeing the area also describe other, often life-threatening, problems that made them choose to leave: widespread epidemics, natural disasters, crop loses, famine, rising prices, land scarcity, and high taxation. Central Texas became a destination for many because of the circulation of letters from their countryman, Rev. Josef Bergman, who had settled in Cat Spring, Texas and written reports of conditions there.2 In 1856 ninety emigrants from Frenstat left in the first wave of departures, including Jan and Ferdinand’s maternal uncle, Alois Klimicek, with his wife and three children. Seventeen years later, Jan and his wife Vilemina, doubtless influenced by letters from their Uncle Alois, decided to join him in Texas along with their four children. They arrived in Galveston on November 7, 1873.

Jan had the perfect personality and physical stamina for a pioneer — enterprising, forceful and energetic. He remained un-deflected by adversity, and tackled the challenges of life with tenacity and a large measure of wit. Ferdinand was the opposite — an introspective philosopher, scholar, and artist of frail health and limited physical ability, whose milieu was the more intellectual climate of urban Europe. He was not at all enticed by the task of hewing out a new country from the wilderness of America.

In 1874 the letters begin. Jan and Vilemina are farming rented land on Ross Prairie, several miles south of present day Fayetteville in Fayette County, a major center of Czech immigration in Texas. The area was originally settled in the 1820s when the first land grants were legalized by Stephen F. Austin while it was still part of Mexico. James J. Ross, for whom the prairie was named, was one of the first settlers. Unfortunately, the family has had a difficult beginning and has been almost bankrupted by crop failures, injuries, and recurring illnesses (perhaps malaria). They are expecting the birth of their only child born in America, my paternal grandmother, Antonia.

Ferdinand and his wife, Anna, are living in Ostrava, a coal mining area. He has a fairly well-paying job as a bookkeeper, but is becoming bitterly dissatisfied with oppressive conditions at his job and the unhealthy surroundings of that highly industrialized city. Whenever he can, he hikes with friends in the mountains and longs for freedom from sedentary work. He sorely misses his brother, and regrets he had not been more forceful in expressing his doubts about Jan’s emigration to America. He is sending money to help the family through the first brutal years.

Jan in Ross Prairie

The following passages from Jan’s letters describe the physical and cultural climate of Fayette County, and the daily life of a Texas farmer in the 1870s.

“You are lamenting that we are living here in a solitary fashion like in a desert but you are not correctly informed about our living conditions and that is why I would like to explain to you briefly regarding our living circumstances. Our neighborhood is populated to such a density that more population here would be detrimental to the same. We live about five English miles away from Fayetteville, which is surrounded by farms for many miles. On each farm is at least one house, some have more buildings but the houses are built as far from each other as possible but each house is by a road so that anybody walking or riding along will come to the house. There are also some larger woods in the broader area but I am not aware of any that would take three to four English miles for anyone to cross without running across a farmhouse in between the woods.

“In our district (Fayette County), which is the size of about half of Moravia, there is about a third of the population from Moravia, a little bit less of Germans and the rest are Americans and blacks. Concerning any worries about evil people we can sleep peacefully around here, it is not even close to as bad as it is in Europe.” (10 August 1879)

Weather. “It is very strange that most of the other people who have come here along with us were able to get ahead quite nicely and were not very often sick. With us it is quite the opposite and especially this year we have experienced all kinds of bad luck. Every weather occurrence was against us. Right during cotton picking the bushes got flattened to the ground and the remaining seeds were still able to grow but it had a bad effect on the cotton quality so that the price dropped from 15 cents to 10 cents a bale. And then on about the 8th of this month the Norther brought such nasty stormy weather with a downpour and hail and wind that it is simply beyond description and I have never in my life seen something like it. It lasted only about a minute but the damage it left behind was huge; it tore down fences, knocked over big trees, one couldn’t tell whether it was the rumbling of the thunder or an earthquake; many houses have been damaged, not to mention the devastation in the fields. We weren’t hit as bad because it didn’t go directly over us but one of our countrymen told me that he was able to salvage only one bale of cotton; that makes a difference of over three hundred dollars. The corn plants were also knocked down, should the fogs arrive soon our damage and losses are going to be great also!” (Late 1874)

Caterpillars. “Then in May we had for several days a blast of cold and wet northern wind; where it had easy access it damaged the cotton and then appeared, as we call them, lice, and that would have been a threat of complete ruin, but the weather warmed up and the cotton recovered somewhat. But there came yet another plague, another brood of caterpillars, not those that devour the cotton very quickly, these were eating slowly but because they live longer they still managed to damage the cotton above our expectations. And as soon as these died they were replaced 100-fold by those voracious ones; then came the drought and crop was done in.” (Late 1877)

Locusts or grasshoppers. “But something else has happened that is for Texas quite unusual. On October 24 billions of small locusts (like our meadow grasshoppers) have arrived; in order for you to get a better idea how it was, they even caused a lot of damage and havoc on the railroad, the trains were delayed by hours because they were slipping on the grasshopper covered tracks. They couldn’t do much damage to the cotton and corn but within fourteen days they had ravaged much of the fodder for the cattle and our fall produce and vegetables, and we can fear the worst in that they have left behind, before they have flown away, lots of eggs that might do much damage in the spring, but it is more likely, as many who have experienced this are saying, that the infrequent Texas winter must kill all of the eggs.” (24 December 1876)

The following year. “The … uniform discussion far and wide across the region has been about the grasshoppers that came last fall from the northwest in endless masses and without any mercy. All the assurances that the countless eggs from the flown-in monsters that might hatch in tenfold numbers will surely be destroyed in winter were useless because with the break of early spring the grasshoppers have begun to hatch and still continue to do so. And should they not disappear by some mysterious means they will again cover the entire landscape, and it seems that the stormy weather doesn’t do them any harm for as soon as the foul weather is gone and the sun comes out with its warmth they reappear in their usual activity.” (24 April 1877)

“Anybody who hasn’t suffered any damage yet by the grasshoppers doesn’t enjoy any respect around here, and has to be ashamed that Lord God doesn’t esteem him worthy enough to inflict him with a cross.” (26 April 1877)

Rain. “I don’t know indeed what else I should write you so that it won’t be a nuisance to you but I will complain to you about our weather. The local system is worse than the weather department of the Austrian government and the rain-office is worthy of condemnation; one could compare it to an alcoholic who is capable for a very long time including the time of need to withhold all liquor and spirits, but when he gives in he unprecedentedly drinks suddenly and at length, and too much! And so it has begun this year again; we didn’t have any rain, at least around here, for about five weeks during a fairly sultry heat period, then on April 22nd it began to rain, the next day it rained very heavily and on the third day it was a regular downpour. …. Just imagine plowed soil in long rows of patches and beds running along a long slope completely covered with the masses of down-pouring rain; where the slope of the fields isn’t too steep they are changed in a few short moments into a lake, and you can easily understand that the soil from the upper part of the fields is washed down and covers the sowing area below with mud. It has caused us a lot of extra labor but this isn’t so bad that it couldn’t get worse.” (25 April 1879)

Drought. “And because of the drought the sugar cane is ripening all at once and we have to keep other labors on hold in order to harvest it; it is already the third crop! My wife is saying: ‘Dear God, how much damage the drought has caused, all the people are moaning and the poor beasts are suffering without water.’ The creeks are running dry and the cows are getting skinny so that pretty soon it won’t be worthwhile to milk them, they are coming back hungry as pikes, it’s no wonder, the pasture is all dried and burned up. But the cows are coming in with their udders all covered in mud, one couldn’t be surprised if they would get stuck. Out there are several quite permanent springs several miles from each other, and the thirsty cattle can smell the waterhole for miles and by their frequent visits the water turns quickly into a very muddy thick liquid and their shuffling and trampling makes the access to the waterhole very difficult so that a cow can get stuck in the mud up to her flanks. If I could make rain as some of the rainmakers do in the wild tribes I would become a millionaire and we could have a hundred bushels of corn more and even the cotton would yield at least a third more.” (27 July 1879)

“The rains here are so localized that on one mile we weren’t able to plow because of the drought and on the other mile we couldn’t plow because of wet. It is always a strange sight for a European to see the neighbor’s field encircled by rain and on his there is hardly a drop of rain as he watches in the sun the storm approaching and going around. Here on Ross Prairie – I am rounding it up to about twenty square miles of area – no other farm has suffered as much from drought as ours.” (29 July 1878)

Poisonous creatures. “There are more than enough poisonous varmints here, one cannot be sure even regarding insects and snakes (but these cases are quite rare), not every snake is poisonous, and most of these critters flee far and wide at the sight of man; I know actually of only one case of snakebite and it wasn’t completely sure if the bite came from a snake. We have here more dangerous critters from God’s creation, for example the tarantula. It is a spider the size of an egg with a velvety surface, it lives in the fields but also this creature shuns man; right in the field, in the furrows, it has a hole straight into the ground, and if a man approaches it crawls into its hiding place, but if we hinder it in getting away or even badger it, it will stand its ground and resist or even jump towards a man and its bite might cause death. But I don’t know of anyone who has been bitten by it. There are many scorpions around here but they sting only if we happen to squeeze them with an exposed body part; its bite isn’t even as painful as a honeybee sting.

“And now I am coming to the most dangerous to man of the creatures in Lord’s creation. Surely not so that a man couldn’t defend himself against it but because it is so small and it contains in its countless legs the most severe poison; it is the centipede, a worm about three inches long and a quarter inch wide, it likes to hide in rotten moist wood or in cracks or in joints of wooden tools or things. We see them quite often even in the house and I am surprised to know of only two cases when someone has been harmed by these little monsters, and the one is an American lady about eight years ago and a German lady recently who have been harmed. The American woman has got off after much effort with her life, and the German woman hasn’t won the battle yet and it looks like she won’t get off without adverse aftereffects.

“The rattlesnake is very dangerous but there are not that many around here, then there is the black snake or moccasin, there are many of those here but they don’t move far away from water; it matches the rattler with its poison. Other critters are more or less poisonous. Here in Texas are also so-called egg-eaters, which remain around human dwellings; they are so called because they swallow whole eggs but it seems that they are without poison. However, one gets used to all this quite well, all this vermin becomes so commonplace that one hardly notices it and we don’t pay much attention to it.” (10 October 1879)

Heat. “Texas has now raging fires, either bad or a bad system, either there is too much rain or too little. In winter it is hot or sometimes it is freezing. Now we are feeling the full brunt of it. Last winter we could not smoke the bacon and the meat without it catching a bad smell, and we have had a drought on top of it. During the February and March turn-in plowing the rains stayed away.” (6 May 1876)

“I am almost convinced that when the Good Lord cast Adam out of Eden with the words ‘In the sweat of thy face shall thou eat bread’ He intended for Adam to go to Texas.” (14 September 1881).

Ferdinand, alarmed by Jan’s stories of the brutalities of life in Texas, urges him to return to Moravia and offers to finance the passage home. A friend in Frenštát has found a job for him to insure income should the family return. “My opinion is this: If you don’t seem to be having any luck and if you don’t expect to get any compensation for your losses then you should return. It’s better for you to be miserable here than over there. It’s better to be poor in your own country than in a foreign one. And if you were to ever gain something over there, do you think that it would make up for all the things you had here and couldn’t have there? After we die can we take anything with us? And what of your children? Will they appreciate you for suffering for them? Who knows whether they would be happier in Europe or over there? And who knows whether they might be worse slaves over there than here even though they probably couldn’t tell the difference because they had never had anything better. The children here don’t perish, the boys get skills which allow them to lead a decent family life, but with girls it’s a little tougher and in America it is tougher still. All creatures have to fight for life and if the fight here is tougher then we learn from an early age to fight that much harder. To suffer all your life for some little hope at the end is pointless.” (4 July 1875)

Jan admits that he writes perhaps too freely about the problems of survival in Texas, partly because he cannot hide the truth about his life, but also because it serves to relieve his anxiety. But he is far from ready to surrender. “We are fickle and unstable as well as insatiable and we pay very little attention to present opportunities and we recognize and appreciate them only in the past. With our troubles and afflictions it is the opposite: we feel them and experience them very strongly in the present but we tend to practically forget them in the past. Therefore we yearn and crave things, we pick over and make wrong choices, and we toss things away, not knowing our position and situation until we arrive at the place where our heart has to be dying of starvation.

“…. But since it has already happened and it cannot be changed for now I would like not to complain about my fate as it is customary here ‘the American way’ because it has been said about the American: ‘He is not alarmed even in the most difficult circumstances, he takes fate as it comes to him and selects out of it the best, he feels within himself the strength to overcome even seemingly impossible things and he tries it right away and if he sees that he cannot manage he will for a while release his anger and then he will go after his goal with a cool head and determined fashion and along the path that is the shortest way to it; he doesn’t despair, doesn’t complain or whine and never ends up helpless.’ ” (Late 1874)

And over time, there is progress, Jan reports. “This year is giving me lots of hope; perhaps the dice will roll favorably. …. the forage work will be more convenient and easy since I have my own wagon! A wagon is not only essential for farming but also very suitable to get to some leisure activities. Before we had gotten one, it was like in a jail for my wife; she doesn’t ride a horse and she won’t take long walks on foot away from the house in order to not leave the children, especially the little ones, unattended. Riding on the wagon is quite neat; it has an expandable boxy trunk instead of the usual sides, and it is very brightly painted, and it is quite pleasant to hold firmly the reins of the horses so that they won’t gallop wanton as they eagerly await the signal to begin the ride. We usually visit the Trnčik, or the Kutač from Horečky, or we are dashing along on Sunday to church in Fayetteville, or to the Lavok Hill church, but mainly we are using it to get together with our neighbors. My wife benefits mostly from this because she can keep an eye on the children and get more out and around with people, and I am glad that I can provide for them such inexpensive amusement.” (7 July 1877)

He also becomes quickly integrated into the American Czech community. His penchant for writing is expressed in contributions to some of the Czech periodicals of the time, Amerikán Národní Kalendář, Slavie, and Slovan (an early weekly published in La Grange). This letter was written to Slavie.

“Esteemed Editors!

A pleasant feeling has to come over every Czechoslovakian patriot who is considering all the benefits provided by the Czech magazines and our dear Slavia to all of us who are scattered about across the ocean by fate and far removed from our core and center, which is our little mother Prague [matička Praha], as long as Czech blood is flowing through him. Every patriot has to have a desire that Czech magazines and publishing, which have come so far by the untiring efforts of the editors, will not only just get by without much trouble, but should prosper.” (29 April 1877)

He writes of Augustin Haidušek, one of the first Czech immigrants to earn a law degree and serve as a city lawyer, mayor in the US, and publisher of the La Grange periodical Svoboda.“Very recently there has appeared in print a new Czech political weekly in La Grange in Texas under the leadership of Haušil and Lidiak who have been born in Trojanovice under Radhošť; with them is active there also Haidušek, an attorney and the mayor of La Grange who is a decisive supporter of the national Bohemian cause3 and who has seen the light of the Lord, I believe, in Spružiny by Hukvald;4 he has arrived here just as a young village boy and has come very far by his own inclinations and diligence. Let there be praise to the worthy humanitarians!” (25 April 1879)

And in the end, he even makes peace with farming. “A fear is getting hold of me that is multiplied by my advancing age that my life will pass and end in a wretched manner, and it seems that time has never before been as precious as now, which I ascribe to my profession. A merchant might lose but makes gains again, sometimes in multiples, but with a farmer it is different; losses are always at hand and gains, if any – one cannot even think about multiple ones – are achieved slowly and carefully over many years when he finds his routine. And yet it is a pleasant feeling to call up from the majestic nature her craft by independent effort, and not having someone else’s calluses on his conscience gives one encouragement and brings sweet dreams, and yet, all things have more or less of the dark side in them. I am lost too much in my ramblings and the end is still far. Should my worries not come to pass I will be able to pass on to you good news. We ought to hope as long as we breathe.” (12 August 1876)

Ferdinand in Ostrava, Frenštát and Retz

In February 1875 Ferdinand tells Jan of a crushing loss — the death of his wife Anna and their newborn baby girl in childbirth. He describes in detail the torturous ordeal, recounting the use of leeches, icepacks, and 12 medications. The baby dies first and then his beloved Anna, after eleven days of excruciating suffering, also succumbs. “– [A]nd the knot which had tied us together was untied forever. The lady who I had loved so much had ended her short trip in this world.

“I could write you much more about it but I hope that you’ll be satisfied with this. I never thought that I would be able to live through something like this. At the time that she died everyone here left and I was left alone. I closed her eyes which seemed to still be so full of life. She was buried on February 16 at 4:00 PM. My friend invited me to stay with him for a number of days. I am going to get rid of this apartment that I liked so much and rent something much smaller. The only plans that I have for the immediate future are that I am going to live alone. I only wish that we could be together to talk. This would be the best thing that could help me after all the suffering that I have been through.” (24 February 1875)

He is longing for his brother’s return and dreaming of a future together. “For the last half an hour I have been absorbed in thought – I have involuntarily quit scribbling on the paper and begun to think whether your situation can be in fact changed, but as when one is suddenly awakened from the deepest sleep by a robust and vivid dream, so have I been shaken up from my musing by a displeasure over an unfinished cause because I have not found anywhere the least bit of salvation and relief. Oh yes, should the possible winning materialize that you have mentioned in one of your letters it could indeed become the sought after messiah. [Ferdinand here refers to playing the lottery, which he mentions in several letters]You would find out the same day or at least the next one that the redemption has come also to us and that I am going to be at your place in three weeks in order to accompany you on the way back to Europe. – Hai! It would be coming via an express train, then on a steamer, and then again on an express train and then via special occasion all the way to your house. What a reunion this is going to be – after so many events and things we have lived through and survived, we are really going to have something to talk about; more than during the last judgment after the resurrection of the dead. – And then we are going to build ourselves a nice little house outside of Frenštát in Paseky Glades and are going to nestle inside and after that we are not going to lack and want anything in this world so that we can expect to be content …” (7 August 1875)

But Jan, on hearing of Ferdinand’s loss, instead wants Ferdinand to come to America to start his life again in new surroundings. Ferdinand replies. “However, America is incapable to satisfy and accommodate me in any case either regarding my health concerns or my chances for earnings even though she has some advantages and good aspects but after taking into consideration her strong deficiencies and flaws they disappear altogether. My circumstances would have to suffer quite a great upheaval in order for me to make up my mind and proceed with the plan to establish my livelihood in America.” (1 March 1877)

Ferdinand suffers a series of illnesses and travels to Vienna for medical advice. He writes about seeing the Emperor during this trip. “Many times while I was in Vienna I saw our Frank [Emperor Franz Joseph] but I didn't even once speak with him. He didn’t seem to be as bad as the mean people say he is. Maybe if he was his own boss then he would do things differently. It seems that he hasn’t yet grown up enough yet into what destiny has for him. I always pictured him as rougher and more intelligent. I also managed to see the King and Queen of Greece at the train station. They are just people like you and me. Our Emperor also welcomed them at the station. I got soaked when I left for home.” (15 April 1876)

In October 1876, on a visit to Frenštát, Ferdinand is introduced by friends to Anna Malcak. They correspond and then marry the following April. Increasingly distressed with his job in Ostrava, he quits, a timely decision, as later he learns that the owner’s son has confiscated the capital of the business and fled the city. This begins a long and unsettled period for him. Marriage to his second Anna seems to have helped heal the pain of his first loss, but Ferdinand is restless. Above all he is determined to escape the “slavery” of working for others. They move back to Frenštát and in 1879 a son, Anton, is born. Settling on the idea of starting a wine business, he spends time in research, then buys a large quantity of wine. When he opens the casks, however, he discovers that most of the wine is bad and realizes he has been duped by the seller.

Ferdinand also loses money in other speculative ventures. “As you must have noticed in my last letter I have not been doing well in Frenštát; I have lost here within the short time we have been living here more than a third of my goods and means in different ways as if all the things that I have touched were set up as a trap for me. I have become very worried about the future because I was afraid that even the money of my wife (about 1,000 gold thalers) would disappear by and by. In the fall I have tried one more time several attempts. I went to Vienna in order to find out and explore possibilities regarding butter and weaving products and goods … .” (24 February 1880)

By March 1880, Ferdinand has abandoned the idea of self-employment and taken a job in Retz (a wine growing region in Austria), working for a wine merchant. He describes a view of the countryside from the northwest side of town. “It takes about six hundred steps and the township Retz along with its long appendage of the Altstadt is lying below you. All around you spreads a very lovely countryside dotted every which way with villages and townships with their whitewashed towers. Toward the west-side of noon (SW) close by on the wooded hilltops are lined up many small villages as if one would be peeking into Bethlehem, – further down toward the noon-side in the distance one can see the Styrian-Alps and on the left side are the Stokerau Hills by Vienna that proceed into the hills coming out of Hungary, on the northeast side are Moravian cities Breclav and Mikulov with its pointy hill and Znojmo in the north and many others. The higher elevation of the hills toward the north is preventing us from seeing very far.

“We are enjoying this beautiful view that I have mentioned above almost every evening, and it is almost entirely our only amusement and diversion. We would be sitting on our favorite spot well past sundown. And when the noise of the working beings around the orchards and around the house settles down, and when the evening breeze brings to the ears of the listeners the peeling of the bells from the many outlying villages and towns in a profusion and variety of melodious accords and harmonies, – it seems then as if nature itself along with her creatures is sending up into the unknown celestial realms, – we are then overtaken by some sacred feeling and spontaneously enraptured as if by the current of praise raising up from below, and we feel then likewise by this solemn moment that our souls are attuned to praising this beautiful creation, and as the dusk is coming down it enhances all of this even more and gives it more reverence and grandeur, and then we lose it all from sight as the view begins to fade while the night is approaching.” (4 September 1880)

Ferdinand’s description stirs nostalgic memories for Jan, who answers. “You have mentioned that I have been describing our landscape and surroundings in vivid colors but there is no comparison with your description! One might think he is reading an excerpt from a work by a novelist, and indeed, I do not understand how, in my age, can so much fantasy and imagination still be present in my mind so that it can hold so many catchy matters and still be easily fascinated and carried away by emotion. I can honestly tell you that I have been fascinated, as I have read your letter (as they say on cloud nine). I could see in my mind every hummock and hill, every little square tower as it is playfully poking through the green trees; how the setting sun is giving the last kiss to the proud Alps and other colossi jutting out above the valley as the melancholy pealing of the bells is fading away in one’s ears. These are the majestic moments in our human lives during which we must forget our hardships and afflictions!

“When I used to have opportunities to gaze into such romantic and picturesque surroundings I have often thought in such a frame of mind: ‘Death is sweet!’ It stands to reason, of course, that such moments are but very short and soon we grow sober. I can see you in my mind as you are returning from your pleasant walks and outings and getting ready to rest as I am sure you are thinking of me also. And even though I am destined not to partake in such phenomena I do wish from the bottom of my heart that you may partake of them to the fullest possible extent.” (6 February 1881)

Jan in Bluff

In December 1879 Jan seeks new opportunity and moves to a house in Bluff (now Hostyn), where the family is at the center of a large Czech community. They rent nearby land for farming and towards the end of the year at a bidding auction purchase 102 acres of farmland midway between Schulenburg and La Grange.

Jan describes their situation. “This location offers a beautiful view for many miles, and the house is about three hundred paces [about 600 feet] from a Czech church, and even closer to a Czech school, and most importantly, it is closer still to the general store combined with a saloon; so I could get drunk daily under the table without worrying too much that I couldn’t find my way home. We respect each other as we have done in the old country. Even though I am not fond of lots of noise I do enjoy association with other countrymen and most of all I am glad for my wife so that she can have here somewhat of a substitute for her homeland.” (Mid-1880)

“… I am gathering that the region around Fayetteville is getting year-by-year more of the Slavic stamp. In the countryside around here it is almost peculiar to hear the English language spoken. Therefore one encounters here people from the old country that have been living here for ten or fifteen years and they can hardly say or understand a word of English, and because they can get away without it the majority shows very little interest in learning it. …. many of the homes around here are in the hands of Czechs and Moravians and also many of the storeowners are compatriots. We have here a Czech school, Czech churches and chapels, Czech clubs and associations, Czech periodicals, even Czech legal representation in the mayor Haidušek in the county seat. Also in La Grange we have the political magazine Slovan. And other enterprises such as the new steam-mills called gins that are used for the cleaning of cotton are also in Czech hands with the exception of the most recent immigrants.

“…. The entire surroundings of Fayetteville, Ross Prairie, Oak Hill, Dale Creek and Warrenton, all of these are like one chain, mostly Czech; likewise you will find a similar situation in the eastern and southern part of the county; Bluff, Vlkov, High Hill, Schulenburg, Mulberry, Velehrad, Nová Praha, one settlement is close at hand to the other, all people there are Czechs or Moravians so that one’s heart jumps up in his chest. The number of Slavic inhabitants in our county is about six thousand souls and most of them are in good standing and are doing well and we even have many well-to-do among us.” (Mid-1880)

Fr. Josef Chromčík was the first Moravian Catholic priest in Texas. In 1872 he emigrated from Lichnov near Frenstat after seeing so many of his parishioners leave. There are several inquiries about Fr. Chromčík in the Přibyl letters. This one, from Jindřich Kostelník, is a request for help in immigrating to Texas. “I also hear many praises about the parson Chromčík, perhaps he could act in my behalf; you must know his reverence personally without a doubt, describe to him the situation and my sad circumstances; or what if I would buy a piece of land adjacent to you or in Bluff – among the people from Frenstat – would I be able to make a living?” (27 January 1874)

Jan comments on aspects of his new life in America, including Politics. “Regarding running for office I have not even tried it and would discourage any such whims in anybody for as soon as one declares himself a candidate he had best not show himself in the open for there’ll be mud thrown at him, and the annoying newspapers and magazines will rain on him reproaches and shame, snooping about his life since the cradle, twisting every uttered word for ill so that the most simple priest could not grant one absolution. And woe unto any candidate, who has in the past let himself, in the least bit, to be tempted by the evil spirit. I only wish that any of the Austrian ministers would be recommended to run for president here. There is no better way for them to have their own knavery revealed.” (26 April 1877)

On food and festivities. “We have spent the holidays joyfully by riding to our neighbors even though similar celebrations and festivities aren’t as festive here as they are where you are; this has a lot to do with the fact that around here we cannot provide our kitchens with the same variety and therefore our everyday meals are, with some exceptions, identical with the festive ones. Should we have fresh vegetables available here year round we might say that we are living like the aristocrats but the housekeeper with a couple of 200 pound barrels of the finest flour, a 150 pound barrel of coffee, a full keg of molasses, with an inexhaustible supply of bacon and lard, and with three to eight milk cows, does often ruminate what to prepare for lunch that day during times when the fresh beef, usually available here in the countryside twice a week, isn’t available.” (25 April 1879)

On the building of his first house on the newly purchased land. “I have to tell you about the manner in which the local houses here are built. The materials needed are wood and nails. We can get at the railroad station all kinds of construction wood in any needed length, width and roughness. The wood is mostly from evergreens such as spruce, fir and pine or as we call it soft wood. The builder needs for his work mainly a hatchet or an axe to hammer in the nails and for some rough hewing and hacking. Forget any carpentry. Then comes the angle-iron and a handsaw to straighten it out, and finally the chisel to dig out the posts and jambs. Completely finished doors and windows of all different kinds are available in stock. Likewise the shingles are precut but they are without grooves, they are actually just sheets of tar paper about 14 inches long and four to ten inches wide and with a wedged thickness so that the upper end is as thin as a paper sheet. The thinner end comes on the top and they are stacked with only two thirds of it with the thicker end sticking out. Because it is layered almost triple way I can cover with three thousand feet of shingles about a thousand feet of roof. The roofers make it completely waterproof.

A carpenter makes one dollar and a quarter per day with food. I have paid him forty dollars for the construction, he has worked on the cottage for thirty-two days. My plan is like this: The core is 48 x 18 feet, meaning two rooms 18 x 18 and in the middle 10 x 18 feet; in front of the hallway a 10 x 12 feet veranda; one of the rooms is remaining in the planning stage till a more suitable time so the entire cottage without the veranda is 28 x 18 feet. It is well built except for the symmetry. The cost including the transport and labor so far is $225 but many things are still missing. I was able to build a shed for cotton and corn seed for $120. The feed and forage for the cattle is stored in a stack in the open. The dwellings here are only for people and not combined with farm tool sheds.” (19 March 1882)

“But the mentioned wood has to be transported for hundreds of miles because the native Texas wood is not very suitable for building houses. Many rafters are completely rotten. The summer last year has been exceptionally dry and many rivers in the highlands have dried up so bad that the logs couldn’t be sent to the sawmills downstream. The demand is huge because of the throngs of immigrants and building of the railroads; all the supply in stock has been exhausted, which is causing a sharp rise in prices. The steam sawmills are located along the big rivers and they transport the wood to the Gulf of Mexico; the supplies in our area come to Galveston and are then loaded on the trains and hauled to the lumberyards at the stations where we can buy it.” (19 March 1882)

On debt in America. “The financial circumstances and customs are strange here, so in order for you to get an idea about the concept I can tell you that many a renter or tenant-farmer here brings his credit and loan to a sum of one thousand dollars and their entire goods and possessions aren’t worth even a third of that; this holds true and applies to the newcomers who have at first bad luck, such do not afterwards recover from this for five, even ten years. One good condition here is that the immigrants get to buy a piece of land (many are still lying fallow) under very favorable terms, so this way many an indebted renter has been able to acquire his own farm.” (20 June 1880)

Jan has a dream of Ferdinand. “Many a time I would have a notion that I see you coming toward me across the fields, that you have surprised me with your visit here. In such a frame of mind it seems only natural and easy that it should happen, and it already came to that that it has to happen, and that there are sufficient means for it. Just as the windstorm blows away the dust even any such ideas disappear, and when the brain comes back to its normal self it is overpowered by torpor. I admit that there exist many means and ways by which we could be reunited again, but their attainment exceeds my mental and physical constitution.” (29 July 1878)

Ferdinand in Vienna

After 16 months of employment, Ferdinand again finds disappointment in Retz. “My employers have described my future position in such a manner that I have assumed that it would be easy to bear the submission and servitude that has in me a bitter and sworn enemy, and with which every employment is more or less connected. And even regarding the work itself I felt justified in my belief that my employment would not be limited only to clerk activities at the desk but would include activities outside mere paperwork and also outside of the office. In these matters I have been wrong as well as in many others. The principal who was and is capable of giving himself the appearance of a philanthropist has revealed himself later as a vulgar lout and even more than that: a swollen-head idiot.

“However, even this isn’t the worst of it. I have been found even here by speculators, meaning privileged swindlers, and contrary to my resolve and despite the fact that I have been burnt and brought to harm before I have been taken yet again for a ride. I don’t want to spend too much time on this because my brain is still reeling just from the thought of it, but it is possible that I am going to describe it to you in more detail sometime later.

“…. My friend, we sure would have so many things to tell one another should we ever meet again in this life! Are we ever going to meet again? – Away with this thought because it is painful; it might be even terrible, more terrible than the awareness that one day we will have to fight with death, and after the fight everything shall cease to exist for us!” (19 July 1881)

By April of 1883 he and Anna have moved again, this time to Vienna. At this juncture, they still have money invested in government securities from which they are drawing interest for living expenses, but again Ferdinand fails to find work. Anna is earning income from needlework and Ferdinand begins to seriously consider the idea of emigrating. “The reason for moving to Vienna was my thought to establish here some kind of existence, but fate has been unfavorable toward me, although I would have accepted any kind of employment, even that of a writing clerk, but I cannot find even that.

“As a consequence of this I am beginning to contemplate America again and I regret that we didn’t leave to go over there already last year! If our situation and circumstances don’t change shortly it could depend on your answer whether we are going to go there or not. That I would be motivated to such a step only by great worries regarding our future, of course goes without saying. However, I know that a man cannot live anywhere without troubles but I am of the opinion that when a man overcomes and survives the first afflictions in America and manages to make sense of the local customs and circumstances he doesn’t need to worry as much about his future as he does here.” (19 July 1881)

In January, 1884, he relates some astounding events, precipitated by a meeting with a certain Baron Dichelburg, who is a retired military officer and a government official. He is seeking employment, and in that era a managerial job with the railroad was equivalent to any state bureaucrat post today, including job security, travel privileges, insurance, and retirement. “So I have taken recourse in newspaper advertisements [to find work]. Through one of these announcements I have been thrown together with a certain baron who was in need of money. He assured me that for a certain financial loan he is going to arrange for me within six weeks employment with the railroad in a definite position as an official. After so many futile attempts this has been a very enticing prospect and opportunity. This man appeared to be nothing but respectable, it could not have occurred to me even in my dreams that I would be so disappointed in him.

“I have converted one part of our securities into cash even though with a significant loss and have lent him the money; in the mean time he has been riding to see us regularly along with another baron who has been kind of serving as his secretary. Within quite a short time all of our money has changed into the baron’s hands (so you can only imagine how skilled he was in gaining someone’s trust), and there is more; during the sale of our last securities the bank has given me 175 gold thalers more than it should have. I have noticed this occurrence the next day when I have been preparing the invoice and the statement; however, the money had already been in the baron’s possession, and even he didn’t have the money anymore. And do you know what? I didn’t have any money to pay the bank back the 175 thalers. But I had to do something. So I went to the bank and told them that they have given me more money than they were supposed to according to the books, and that I am unable to bring it back right away since I have already given the money away and I have obtained a six months grace period to pay it back.

“This was the first worry because the following things were beginning to go through my mind: what if I won’t be able to get that employment and then the baron won’t pay me back in the appointed time. And soon enough the second worry did appear. Not long after this I have found out that the baron is not going to keep his word regarding the employment – and then other things weren’t happening the way as they have appeared at first. Admittedly, I have in my hands the obligation note (only for 2,800 gold thalers) and for the 900 I have only a bill of exchange; [this amounts to about 5 times his annual income], a note according to which I would have the first right to use it against his estate should he fail to pay me back by November 30th; however, my trust has disappeared.

“I have rendered to you in rough and short outlines the account for the cause of our current situation; – I don’t want to describe to you our torment because you can easily imagine that as we have watched our entire fortune getting practically lost, not having any money at our disposal, to be in Vienna empty-handed without work and income, and to be used to better circumstances because of our thriftiness and frugality, it has been for us an unbearable idea! However, we have survived it as far as I am concerned but I am surprised that I have survived this; – so that now I am ready for anything!” (1 January 1884)

Within the heart of every human, there dwell incomprehensible mysteries of being. We will never know the reasons why a man of thoughtfulness and intelligence such as Ferdinand could allow himself to recklessly succumb to the ruthless wiles of swindlers and cheats, not just once, but three times. Perhaps it was excessive gullibility combined with unfortuitous circumstance, or maybe it was simply his driving hunger for liberation from servitude that drove such actions; whatever the reason, it is probable that only extreme occurrences could have caused him to at last seriously consider the momentous decision to leave his homeland. Shorn of their money, Anna teaches Ferdinand to sew, crochet, and embroider and together they earn enough to barely pay expenses. Eventually he finds part-time employment with a lawyer, who helps him pursue a legal case against the baron. During the next year and a half they delay, waiting for the case to be decided. They move from place to place and from job to job, and vacillate continually about emigrating.

Anna is fearful of the ocean voyage, and Ferdinand comments. “I am not able to discuss much with my Anna regarding America; she is imagining the voyage as nothing but terrifying and difficult. If I only could transfer her in her sleep all the way over to you, she wouldn’t have any longer any objections about America.” (6 February 1884)

Ferdinand is concerned about getting ill in Texas because of its conditions that he describes as “…so repulsive to the regular health and hygiene of our people.” (25 November 1882). Because he suffers from a heart ailment he thinks that he has not the physical stamina and strength necessary for farm work. Their only child, Anton, is only five and too young to help with the labors of farming.

Nevertheless, Ferdinand asks many questions. “How much would a small farm in your vicinity cost? (Of course, in our current circumstances and with our prospects it is a rather silly question). How much would be the lease or tenancy for a small farm? Is the rent due beforehand or in arrears? Do you keep cows, chickens, etc.; what are you doing with your milk and butter? You have already mentioned to me that regarding clothing it is practical to take only the bare minimum and necessary stuff; but what about underwear, bed-linen and linen, extra down comforters, and with other similar items and things? I also have all sort of books, one of them is a good medical book, and I also have some carpenter tools.” (1 January 1884)

In September 1884, the court case with the baron ends with no restitution for Ferdinand and the baron flees the country. Ferdinand writes. “Here I have nothing good to look forward to; a fully mature person has a hard time to find a good employment. The protective dike that has taken so many years to build and finish with the purpose of protecting my wife and myself from poverty and want when the days and the years of weakness and illness would come has been breeched and torn down and there isn’t any hope of a possibility to ever, even if only partially, to rebuild it. My star has already descended and, therefore, one cannot wonder that some moments are coming within which I am looking into the future with fear and anxiety.

“After all it has been said that man has only himself to blame for his misfortune; therefore, even I have to assume responsibility for the consequences arising from that affair and, burdened by my guilt, keep walking through life toward the end that has been appointed to all of us. However, I am conscious of this, that even during our good financial times I have hardly ever let loose the reins of frugality and thrift, and should all other fellow-human-beings be of my disposition, temperament and nature, no one would ever meet with such a manner of misfortune as this one.” (8 September 1884)

Attempting to earn money to pay for the journey, in early 1885 he finds a full-time job, but it only again fuels his vacillation. In the midst of their preparations for departure, he is still clinging to the possibility that he is exaggerating their problems and that they may not need to take the fateful step. “Regarding our unsettled and undecided situation you cannot be surprised or marvel over it. That I have not yet carried out my intentions already a year ago has been caused, as you well know, because my circumstances have been assuming such a form that it awakened a hope within me that I might not be forced to make that decisive step after all, which you have called – and justifiably so – a game of chance. Now I do have an income even though insecure and earned in a bitter fashion, but even such circumstance that I have employment at all is sufficient to provide my hesitation and doubts with more food.” (18 March 1885)

But this employment too becomes intolerable, and he begins to prepare seriously for the journey. “I couldn’t stand it in that hole any longer. As I have already mentioned to you it was hardly possible just to turn around in that room, the windows have been completely lined with brickwork and cannot be opened. The office door leads into the warehouse [manufacturing wool dyes] that is also completely isolated from any whiff of fresh air from the outside. How nasty and disgusting it is to be in such a room and also how harmful to one’s health it is can be appreciated only by someone who has experienced it firsthand.

“And so I am going to give it a try and have a go at it in America. I know that no prosperity is awaiting me there, on the contrary rather troubles as it is here, only in a different way and of a different kind but I am prepared to endure even worse conditions. If nothing else then at least our boy, should he grow up, might not have to be such a slave as he would be here. We are already making ready for the journey.” (27 April 1885)

One can imagine the mixture of compassion and dread that Jan must have experienced on hearing the ever-worsening news from Ferdinand — the brother who had been his own support in times of extreme trial, was now reduced almost to penury.

Yet Jan is ready and eager to assist him with advice and help. “So, you think it might be silly that you’re asking me so many questions? I can assure you that I would be much more worried if you wouldn’t ask me any questions at all because that would give me a reason to suspect that you might be taking such serious matters very lightly and carelessly. I think I might be writing you again even before I get an answer to this letter. However, don’t wait with your reply till you get the second letter because we would gladly hear about your progress regarding this expedition. .… It is too bad that you didn’t depart earlier during the price wars among the shipping companies. The price for a grown-up person from Hamburg or Bremen was then only ten dollars; now it has risen to 18 dollars to New York.

“…. Write to Kares and Stotzky [apparently the first Czech emigration company] in Bremen so that you might get more familiar with departure schedules and don’t trust any shady and fly-by-night agents; such have left already many in dire straits and so destitute and penniless that they couldn’t get here or get back.” (4 May 1875)

Ferdinand, Anna and Anton arrive at the port of New York on May 10, 1885.

Jan and Ferdinand in Texas

During the first two and a half years after the family arrives in Bluff there is no correspondence because they are living with or near Jan’s family. Later letters indicate that they had learned to farm and that Ferdinand may have secured a teaching position. Then, from November 1887 to November 1895 there is another series of letters from Ferdinand only, to Jan. He, Anna, and Anton have moved to halletsville in Lavaca County. Here they are in frequent contact with their Uncle Alois (mentioned earlier) who was the first recorded Czech immigrant to Lavaca County. In the fall of 1887 Ferdinand has taken a teaching position at Sacred Heart Catholic school in halletsville, founded in 1882 by Sisters of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament from Lyons, France.

He was probably hired by John Anthony Forest, one of the “Apostles of Lyons,” a group of seminarians, who in 1863 emigrated when Bishop Claude Marie Dubuis of Galveston asked for missionaries to Texas. Fr. Forest served the Lavaca County area until 1895, when he was appointed bishop of the San Antonio Diocese. His tenure saw the expansion of many Catholic and charitable institutions throughout the diocese.

Ferdinand describes his position. “The teaching at the school is very easy, lasting from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM but the rest of the time I spend learning English, which is hard. After school I go to the convent where I read Czech books to the nuns and they in turn teach me English. This lasts until 6:00 PM. I practice English at night and do some homework for the convent. I do the same thing in the mornings. Saturdays and Sundays are about the same except for the frequent visitors which interrupt me. In the beginning it seemed sort of lonely and sad here but we have gotten used to it. I am teaching 20 children at school, 19 Czech and 1 German. There are also 3 Germans and 1 American but they left after one month because of the school strictness. There was also another Czech who left because he didn’t learn anything after six weeks. Our Tonek used to go to the convent to learn English but quit because he didn’t learn anything. My wife doesn’t teach in the convent because Czech isn’t being taught now.” (26 November 1887)

Five months later the job seems tenuous. “Today it is 5 months that I have been teaching school and I still have 3 to go. Right now I am teaching 17 students but in a number of days that will drop to about 4. After that Mr. Forestwants me to go out and teach children in the country but I don’t think the country children would have the time with all the farm chores. I don’t think that I will last very long on the money I’m making now and Mr. Forest says that he can’t pay me any more because the students’ parents are already behind in school payments. The money they are paying me now is insufficient and I don’t know when the school will get enough money to pay me the rest of the balance.” (17 March 1888)

His attempts to learn the English language are frustrating. “I have given all my spare time to learning English but it isn’t easy for me. I knew that there was a big difference between spoken and grammatical English but I never dreamed it was so different. An English person speaking English would have trouble communicating with an American who has learned the American vernacular. A person wanting to properly communicate with Americans in both speaking and writing would just about have to learn 2 languages. You could only achieve this if your work permitted you to frequently speak with other people. It is impossible to learn from a book the right way to pronounce words correctly.” (17 March 1888)

Teaching does not pay sufficiently to support his family, so he and Anna decide to rent land and take up farming, which gives them a better income. In 1888, an important event for our family is their adoption of Anna’s orphaned nephew, Albert Stockbauer (my paternal grandfather). He lives in Netolice, Bohemia, is only 9 years old, but is courageous enough to undertake the journey to America with no other family member accompanying him. On the trip over, he finds misfortune at every turn — his caretaker abandons him en route, he loses his luggage, and ends up in the wrong town in Texas. Ferdinand finally locates him and brings him home.

He describes their first meeting. “You can’t imagine what a person looks like after traveling for 41 days without a change of clothing. When he arrived he became ill. He is now feeling better though. What will come of him we will soon see. He seems to be a strong person. He’s half a head taller than Tonek. He has strong bones and good healthy color.” (12 December 1888)

Many letters from this period are communications with Jan about finding land where they can be closer to one another and farm together. In 1891, Jan finally purchases 500 acres of prairie land in Victoria, Texas. Several years later, Ferdinand and Anna purchase from him 80 acres of this parcel and move there in 1895. Finally both families have established permanent roots close to one another. For Jan it must have been a bittersweet victory, because his Vilemina died in 1894, only 3 years after the land was bought. The Jan and Ferdinand Přibyl letters end in 1896.

Epilogue

Albert Stockbauer, the adopted son of Ferdinand and Anna, married Jan’s youngest daughter, Antonia, and the two of them took over managing the Victoria farmland from Jan. They had six children (my father was their youngest), but in 1918 both Antonia and the oldest daughter, Minnie, died in the Spanish Flu epidemic during WWI. Albert, the oldest son, remained at home to help his father with the farm. Antonia’s sister, Lebussa, and her husband, Wilhelm Baass, took in the others.

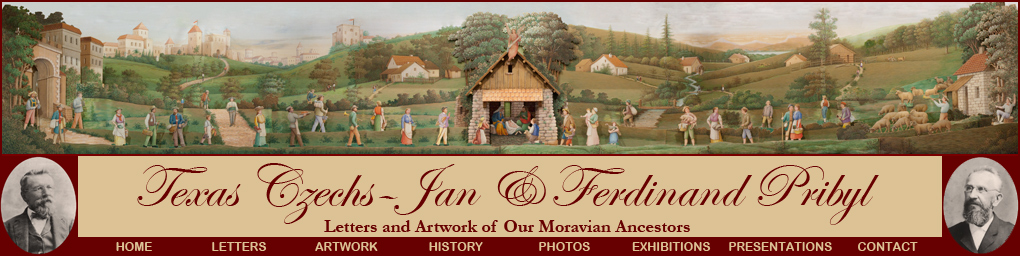

In his later years Ferdinand became an accomplished artist. Some of his paintings are landscapes depicting Moravia, but most notably he produced impressive wall-mounted, three-dimensional nativity scenes that were 10-20 feet long with several staggered layers of scenery and figures. They depict the Holy Family in a stable and villagers streaming in from the countryside, bringing gifts to the manger. He produced about seven of these for family members, who continue to display them.(The Bethlehem scene, now owned by Elizabeth Stockbauer, may be seen at www.ornamentalturner.com/Přibyl/).

Ferdinand died in 1915 and Anna in 1927. Jan died in 1925 at the age of 94. Among the letters, there is one posted from Frenštát in 1921 in celebration of Jan’s 90th birthday, signed by 22 members of the Citizenship Club of Frenštát, a fraternal organization he had helped found as a young man. The letter contains this message: “To the oldest living member, we hope that you will reach 100. We wish you good health and quiet contentment in the midst of family.”The people of Frenštát still remembered their old friend, Jan.

NOTES

1. The Jan and Ferdinand Přibyl letters quoted in this article were translated by Robert Santholzer and Thadious Polasek.

2. See a translation of Bergmann’s letter in Kosmas 20, no.1 (2006): 40-47. See also David Chroust’s article on Bergmann in the same issue.

3. I consulted the following works for background information about Czech immigration to Texas: Clinton Machann and James W. Mendl, Jr., Czech Voices (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1991); Machann and Mendl, Krásná Amerika: A Study of the Texas Czechs, 1851-1939 (Austin: Eakin Press, 1983); and Drahomir Strnadel, Emigration to Texas from the Mistek District Between 1856 and 1900 (Victoria: Kurtz Printing, 1996).

4. Liberation from Austro-Hungarian rule in Vienna.

5. Villages near Frenštát.